Ask a Badass is an advice column answered by history’s hidden badasses, writing as they see their whole lives and our modern world.

Dear Badass,

My New Year’s Resolution for 2020 was to make time to meditate, read, and write. When everything happened and I found out that I’d be working from home while my city sheltered in place, there was a grimly amused part of me that thought I’d be getting my wish.

It’s been more than a year and I feel like I haven’t done anything. Some weeks are better than others, but I’ve mostly had to drag myself through the work I had to get done. For the rest… I’m watching a popular show I didn’t have time to watch when it aired years ago. I’m rereading fantasy books I’ve read before. I’m not even letting myself alone with my thoughts, much less meditating. I have story podcasts on constantly.

I’m not even sure what to ask. Am I broken? I look at social media and it seems like everyone has moved forward in the past twelve months while I’ve barely managed to keep my place. I’m climbing the walls, but I’m also afraid of when I have to go back into the world.

What should I be doing?

Where Did the Year Go?

Dear Where Did the Year Go?,

Sometimes our external circumstances perfectly match our internal ones. It seems like you are not so much locked in your house but in your ideas. You could be standing at the front of ship cutting across the North Sea and still be just as stuck. I spent almost 60 years bricked into a small room, but I was never disengaged.

After Midday prayers on most days, people would walk up to my window and ask for advice. They said I lived close to God and He is the Truth, so I was closer to the Truth than they were. In fact, I just had time to think about things. The people of Utrecht spent so much of their lives trying to escape one of the Four Horsemen. If Death came not by War, he came by Pestilence or Famine. Or riding the floods that were more dangerous to our Low Countries than any Burgundian army.

I don’t know if I bricked myself away to escape the world or my father. I felt so logical as I paid to have a tiny cell built into the Buurskerk. I chose it for its beautiful choir and its relative unimportance. It was not the biggest church in Utrecht. That was the Domkerk, the province of my father and the partisans he fought with – and against.

I thought that by locking myself into that cell for prayer and contemplation, I was devoting myself to God. I stayed, however, within the city that I loved. I had a window on a busy street that I opened for food and waste and, yes, to talk to my fellow citizens.

I think I sought safety as much as devotion. I had been happy living among my sisters in the convent, praying and doing good in the community. When my father rallied priests and nobles to fight the Burgundian takeover, however, I could see only death awaiting my family.

If I hoped that locking myself away from the affairs of men would save me, I sorely misunderstood the danger. Utrecht was besieged, once then twice. Invaded or liberated again and again, depending on who you supported, in an endless cycle until the ordinary citizens wanted nothing so badly as an end. And through it all, I was locked in my cage, dependent on the faithful for my daily food.

There were days when prayer was hard. The faith that had been a roaring fire throughout my life sometimes dimmed to a candle. I matched the spiritual suffering with physical. I went barefoot without heat and eschewed meat. I held the stations of Christ’s passions for hours, keeping myself in the most uncomfortable positions thinking about the suffering on the cross.

One day, when I was lying facedown on the cold stone floor with my arms outstretched, I suddenly saw an image of Mary the Mother. Not as she stood at the foot of the cross, no. I saw her as a mother with her newborn child. Words came to me, just a line of text. When I wrote them down, more followed. In doing so, I wrote a joyous song of love.

As I continued to write from my cell, I began to see a new portrait of my city. In those horrible years as my Utrecht was ravaged by opposing armies, we all gave up our illusion that we knew what the future would hold. The men and women who came for my advice did not ask me the fate of the wars or the crops. They asked about matches for their daughters or apprenticing their sons in a trade. They wanted to know how to get along with their in-laws and whether it was a sin to love a cat as if it were a child.

They did not find joy despite the terrors around them. When they lost faith that the future would be safe, they threw themselves into the days that they were living. Suffering for the sake of future happiness no longer made sense without any surety of the future. So they instead sought to live each day.

There is nothing wrong with what you are doing now if it made you happy. Since it doesn’t, you must seek to find another source of joy. Your habits of disconnection seem designed to make you feel little. What would be for you what my prayer to the Virgin was for me? If you don’t know what would connect you and allow you to see beyond your cell and self, that is a cue to try more things rather than give up entirely.

A word about your reading and watching. Any tool that helps you survive a pestilence is a blessed one. Your resolution for action assumed a future that did not exist. You owe nothing to your former decision.

I do believe, however, that if you truly wish to meditate and write, you must first allow yourself to feel pain and fear. It will not overwhelm you. You may even find some hope to carry you into the future.

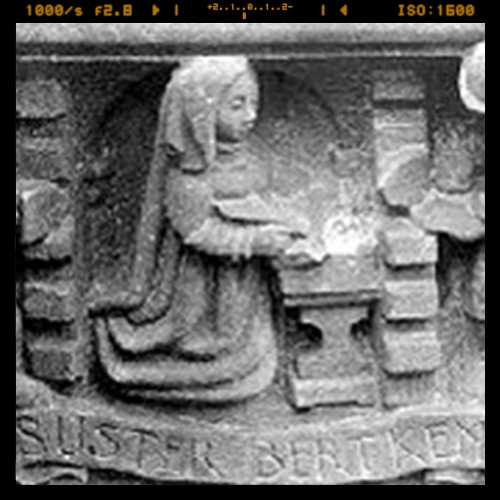

Berta Jacobsdottir, known as Sister Bertken

Born in Utrecht around 1426 to a canon from one of Utrecht’s leading families, Jacob van Lichtenberg. Died in Utrecht in 1514 and was buried in her cell. After what appears to be a good education and some time in a convent, 30-year-old Berta paid for a cell to be built for her attached to Utrecht’s Buurskerk. Anchorites were more common in convents, but there are other examples of urban anchorites like her. What makes her unique are her beloved religious writing, which went through several editions by multiple printers, and her personal popularity, which led her to be consulted during her lifetime and remembered via monuments to this day.

You can find out more about Sister Bertken in the incredible Vrouwenlexicon.

Fill out our form, and we’ll let you know if one of the badasses responds!