Ask a Badass is an advice column answered by history’s hidden badasses, writing as they see their whole lives and our modern world.

Dear Badass,

It’s time for adventure.

I’m 26 years old, and I’m done with my small hometown. I need to get out and see the world, and I’m not just talking about going to New York or Chicago or LA. I want more. I want to sit next to the Seine, drinking coffee and eating a crepe. I want to climb through jungles and explore hidden temples. I want a smelly camel to pass right in front of my face.

And I want your help in doing this. How do I do this? I have enough money for maybe a full week of adventure, but how do I make this an indefinite journey? I’m sure there are people that just pick up and move without any assurance it’s going to work out. I bet some of them have to go back home, but I bet there are also some that figure it out. How do I become one of those?

Give me some of that badass advice and inspiration, and I’ll give you the next adventurous badass to write for your column.

Sincerely,

Packin’ My Bags

Dear Packin’ My Bags,

I leaped into a terrifying voyage at an age when most women in Troyes were settled with children or surrounded by convent walls. I suspect my sisters feared my sense had at last forsaken me. Or maybe they knew that I had at last found what I’d been seeking. I had always felt the pull of something larger than myself, but I did not know how to call it. A lifetime of service and prayer had left that space in me unfilled, so I seized the challenge of crossing an ocean to make a colony of a hunter’s camp in the New World.

I was utterly unprepared for all that I would be giving up. I wouldn’t have said I grew up rich. As the country daughter of a royal minter, I knew what the nobility had that we didn’t. When I first joined the confraternity of Notre Dame de Troyes, the austerity of the nuns’ lives first shocked, then appealed to me. When I began to serve the poor on their behalf, I saw a life even starker, in which starvation stalked the footsteps of each day. None of that prepared me for life at Ville-Marie, a tiny for on the island of Montreal.

The rules of 17th-century France had stifled me, but they had also protected me in ways that I did not realize until I went without them. There was no power of the church to fall back on, no protected place of social chivalry. The winter landscape was trying to kill each one of us and only by fighting with all our strength every day were we able to survive long enough to build a community. Later, I made the voyage with girls who were utterly unlike me, but equally flinging themselves into the blank space of the unknown. The filles de roi were largely poor girls from Paris who had been paid to leave everything they knew to create families on a tiny island in a winter river.

I do not know the mechanism that will enable you to afford your travel, but I can tell you how to live abroad. Be willing to change your style of living, but hold fast to the things you most care about. I gave up my favorite foods, my style of dress, my secret luxury of reading by the fire, and forced myself to never look back. At the end of eighty years of life, the first thirty-two seemed like a dream, or a story I’d read in a book. Surely I had never lived in such ease. But there were some parts of me that were always there.

I always fought for education, first my own, then for the poor of Troyes, then for all children of the colony, regardless of sex or birth. The woman who chose to leave for the colony would’ve been proud to know that the order she was one of the few places in New France were English, French and native women would intermix. My need to be useful was what first drew me to serve in Notre-Dame de Troyes. When the order I built in Ville-Marie was stable enough to draw the attention of the bishop and he ordered us to cloister ourselves, ending our school and ability to interact with the colonists, I crossed the ocean again and got permission from the Sun King himself.

In all, I crossed the ocean seven times, braving pestilence and shipwreck. Like all well-raised girls, I was raised to believe I needed the protection of society’s walls. I was able to mother a colony only because I faced down those fears. You must find what you were raised to fear and move towards it. Give up any idea that you can prepare yourself for your new life. Some of the big things will feel shockingly familiar and some of the small differences will be unexpectedly devastating. There is no preparing for change, any more than a ship can prepare for the next wave. You can only ride it out and keep your compass set for your own personal true North.

May God and Saint Catherine look over your journey. I certainly will.

Saint Marguerite Bourgeoys

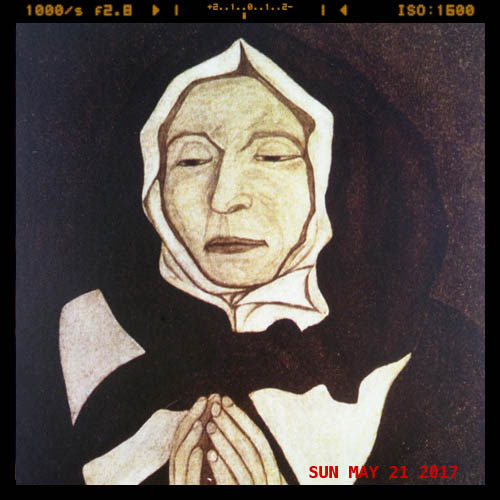

Born in the French town of Troyes on April 17, 1620, the seventh of the thirteen living children of Abraham Bourgeoys and Guillemette Garnier. Died of a fever on January 12, 1700, in Fort Ville-Marie, New France. At age 32, after twelve years of uncloistered religious life, she volunteered to go to the tenuously held army base of Ville-Marie to begin a school for children. She made the dangerous Atlantic crossing seven times, to bring recruits for the order and the beg protection of the French king. The congregation she fought so hard to build still stands in Montreal and she was canonized by Pope John Paul II.

Fill out our form, and we’ll let you know if one of the badasses responds!