Ask a Badass is an advice column answered by history’s hidden badasses, writing as they see their whole lives and our modern world.

Dear Badass,

I know a lot of us are scared right now and a lot of people are facing a bigger threat than me. I can’t help it though, as a woman online and in the world, I feel so targeted. There’s just been so much ugly stuff said about women this year and it feels like it’s getting worse. My parents are saying “we survived Reagan and Bush”, but that rings hollow. What should we actually do?

What Now?

Dear What Now?,

A sense of history can be instructive. The sentiment “we’ve survived similar” ignores the millions who died in a misled war or in an uninvestigated epidemic. It also assumes that the future will be no worse than the past. I will make no promises to your future. I can tell you how I was treated by men of power when they thought I had none, and what I did in response.

I do not remember my father, but I am certain that he was a man of colossal faith or unremittent ambition. Despite generations of French kings maneuvering for control of Flanders, he left the duchy to his pregnant wife and infant daughter to go on Crusade. My mother was a kind woman, but fanatical for my father. When my mother had delivered my sister safely and fully recovered herself, she embarked on the dangerous journey to meet him. When she landed in the Holy Land, she heard that my father had been proclaimed Emperor in Constantinople, but she died of an illness before reaching him. The following year he was lost in a battle for his throne. For the rest of my life, I carried the name of Constantinople, the city that orphaned me.

My sister and I became wards of the expansionist King of France. As soon as I bled, he married me to the son of a family he needed to appease and sent us to administer Flanders for him. He thought because we were young, my husband a foreigner and I a woman, that we would be harmless. I wish I could have been the one to tell him that we raised an army to drive him from my homeland.

I was fourteen when my husband was captured and the French King sent an advisor to guide my rule. The French had won for now, but at least I could help my people. Without drawing French eyes to the deed, I granted charters of self-governance town by town and reformed laws to apply fairly. Under the guise of piety, I created the first places where a woman could be master of her own destiny. I founded female monasteries, the first in Flanders and Hainault. I went further, supporting Beguinages, a new type of community where women could live together without taking vows or giving up their families. Their only requirements were working for the poor and living for the spirit. When I was born, a woman had nowhere to go if she did not want to marry where ordered and bear children every year. When I died, she had dozens of places across Flanders and Hainaut.

The tragedy of man is how easily greed and misplaced faith can overwhelm his best interest. Some of the townsmen I did the most for were the first to the front when the crusade against me began. A man appeared in the fringes of my tiny kingdom claiming to be my father. He made no attempt to contact me or my sister, but instead gathered an army to drive me out. He preached that women were created to serve men, not to lead them. To the Flemish, he promised that he alone would fend off the French depredations. I do not know what he said to the French nobles scattered across Flanders, but they did not give him money in the belief that his first act would be to drive them from power.

I was bereft, holed up in Mons, the single city that stayed loyal. I cannot tell you how desperately I wanted to leave them all to the fate they’d chosen. I’d sacrificed to give the townsmen and women some measure of freedom and they deserted me for a man notable only for hateful words. I just couldn’t bear to hand the communities I’d made over to a con man. If nothing else, the Beguinages would be destroyed and women would once again be forced to choose between vows.

I made a deal with my husband’s jailer, the French king, and got my kingdom back. He publicly met with the pretender and exposed him as a fraud. The cost of his support was high, but the cost the madman would have exacted from the people of Flanders would’ve been higher. Besides, before his capture, my husband told me the story passed around the ruling families of Europe: Tsar Kaloyan had executed my father and used his skull as a drinking cup. I could not bear to let someone profit from my father’s horrible fate.

What do I learn from my story? Those in power will ignore the disempowered. That leaves the excluded and those of conscience with two imperatives: help where you can and fight where you must.

I did not support the Beguines because they were like me. My people defined themselves by class, then faith, then family, and only then by sex, if they thought of it at all. The Beguines were often poor women who did not fit into any definition. I supported them because like me, they were disdained by men of power. In an unjust system, it is incumbent on all of us to help each other, to the full extent that we can.

When we must fight, we must not shrink from it, no matter the cost. We did not choose the fight, but we can choose to meet it forcefully, secure in the knowledge that those we have helped will pick up the banner when we fall.

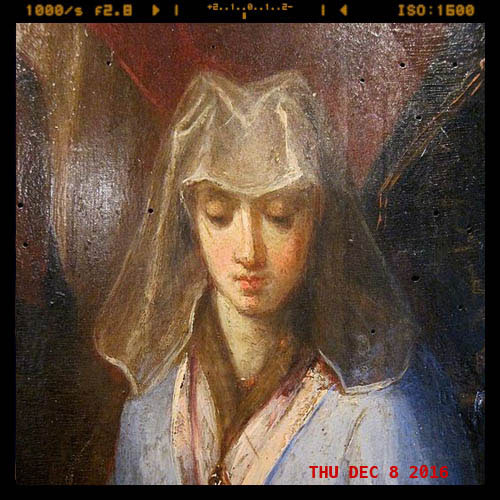

Joan of Constantinople, Countess of Flanders and Hainaut

Born around 1200, likely in Valenciennes to Count Baldwin of Flanders and Hainaut and Marie of Champagne. Died on December 5, 1244 in the Abbey of Marquette, a monastery she founded in a town she fought for. After the false Baldwin was unmasked, Joan forced the French king to release her husband by petitioning for an annulment and making overtures to an anti-French power. They ruled together until his death and when she remarried, it was to a husband who supported her but was largely absent. In addition to expanding the power of towns and religious institutions for women, she was a patron of authors with several books written to her and the first novels in Dutch written during her reign.

For more on Joan, check out her letters on Epistolae.

Fill out our form, and we’ll let you know if one of the badasses responds!