Ask a Badass is an advice column answered by history’s hidden badasses, writing as they see their whole lives and our modern world.

Dear Badass,

I work in entertainment and harassment has just been part of my life since graduating. And not even just harassment, that thing of trying to convince people whose help you desperately need to see you as a human being. Everyone tells us to get mentors, that you won’t succeed without a mentor. Men are like 90% of the higher-ups, but most of them see young women as sex objects to pursue or avoid being alone with, not as someone whose career they can take an interest in.

I don’t personally know any of the people who’ve made public accusations or the people they accused, but every story that comes out seems to bring up so much inside me. Like I try to be hopeful that any consequences might make other predators think twice, but every time I go online it reminds me of so many frustrating and difficult times. And if one more guy that I know for a fact had heard me talk about getting harassed says he had no idea it was so bad until #MeToo, I think I’m going to push him into traffic. I feel myself getting angry every day. What do I do?

Fuming At My Industry

Dear Fuming at My Industry,

Allow yourself a space to get all the way mad. You can rage or curse or weep or scream. Whatever you do, make it sharp and loud. Do not hold back. Do not try to soften its intensity. Let the fire cleanse you of any lingering debris of guilt or shame. Let your spirit convince your heart and head of its innocence. When you are done, you will still be a woman in a landscape that was not designed for you. So you must plan.

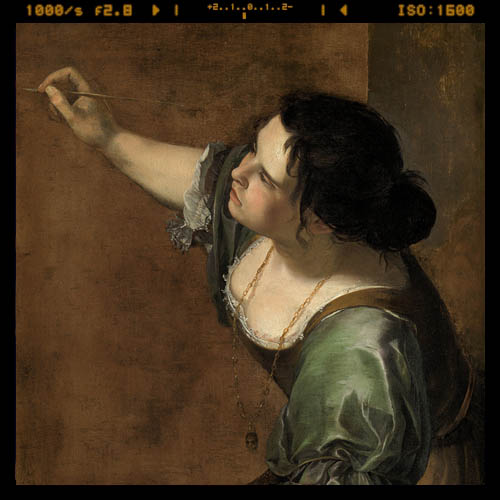

I was not the first female painter, but I was one of the first to support myself with my paintbrush for my entire life. That didn’t happen because I was a talented painter – though I was – it was because I was good at the business of art. I could see myself and my work through the eyes of my patrons. I knew how to get them to buy a painting from a woman. Sometimes I hated it. Sometimes I could not help but compare my career to the men I knew, to imagine what I could do with all the time I wasted working around the ignorance of men with money.

If you were to look at two lists, one of Rome’s rules for women and the other for men, you would wonder if they were part of the same world. Caravaggio stabbed and fucked his way across the cities of Italy and he was beloved by the Pope. Women, however, were considered soiled just for being in the company of men like him. My father’s studio offered me the chance to develop my skill, but it also exposed me to danger while depriving me of the means to defend myself.

I was assaulted by one of my father’s visitors. My father brought charges against him only when he refused to make restitution. The rapist argued that I was already tainted, given the models and painters that frequented my father’s house. It came out in court that he was already accused of rape and suspected of murder, but I was still tortured to be sure I wasn’t lying. My fingers were eventually able to hold a paintbrush again, but the court failed to enforce even the measly banishment to which they’d sentenced my rapist.

I married a Florentine to get away and build a career there. They knew, of course, about the trial. Such a scandal was delicious to wagging tongues. Everyone expected me to hide my shame, but instead, I flaunted my rage. I painted the incompetent judges as the elders leering over Susannah. I painted Judith as she cut Holofernes’ throat and later, as she escaped with his head in a basket. I painted Jael poised to drive a nail through the skull of Sissera. I painted Lucretia and Cleopatra, who used even their deaths as weapons.

It is true that I let my brush express the rage in my blood, but the paintings fed a public appetite. My reputation grew, as did my commissions. Had I moved to Florentine alone, my wealth would’ve grown as well. My husband gave me a daughter but spent all my money before I’d even earned it. I took my daughter and left him my debts. I would go to Naples, Genoa, back to Rome, and even to England without ever returning to Florence.

I do not know if I would have been able to leave him, had I not already faced a far worse judgment. I do not know what I would have been able to create in my lifetime if commissions had been thrown at me, as they were at Caravaggio. I spent so much time coaxing each patron and payment. I have wished so desperately to be born into a different shape or a different world.

The world did not change, but I did. Each fight left me stronger and smarter. I know you would not choose your fight, but it faces you nonetheless. All you can do is meet it so that it hones you.

Artemisia Gentileschi

Born in Rome on July 8, 1593, to Tuscan painter Orazio Gentileschi and his wife Prudentia, who died in childbirth when Artemisia was 12. Died in Naples after 1650, likely of the plague that decimated Naples in 1656. Artemisia was a successful painter of the baroque period and one of the first European women to support herself throughout her entire life through painting, if not the first. Even in death, the assault she suffered overshadows her reputation, but she had a long and successful career that brought her to Rome, Florence, Venice, Naples and even the royal house of England. As was fashionable at the time, her work uses dramatic poses, known stories, and light and shadow to create dramatic effect, often with women as central figures.

Fill out our form, and we’ll let you know if one of the badasses responds!